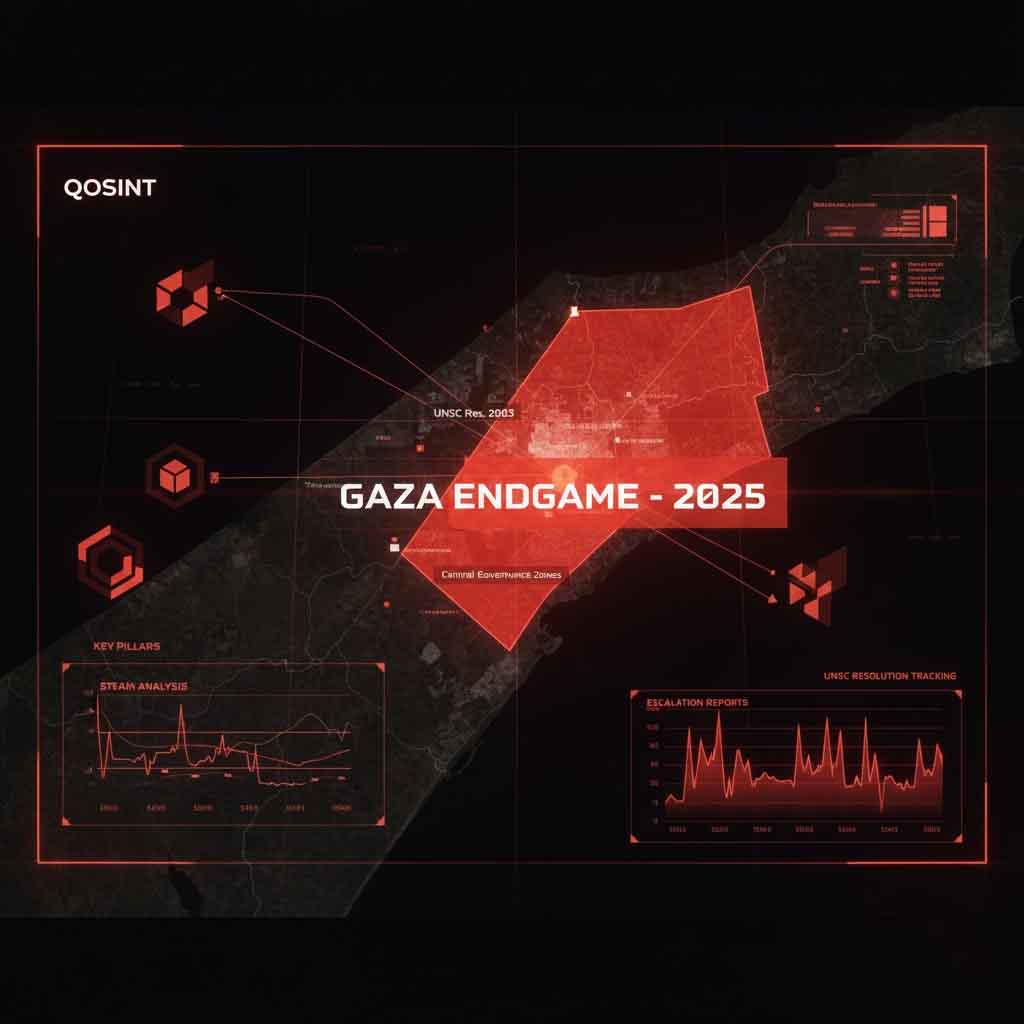

The Gaza Plan at the End of 2025

The Gaza Plan at the End of 2025: What Really Stands Behind the “Road Map” — and Why Its Core Pillars Are Already Under Strain

By the end of December 2025, the phrase “the Gaza plan” has become a convenient umbrella under which a wide range of documents, diplomatic initiatives and political statements are often mixed together. In reality, this is not a single text, but a complex construction. At its core lies the so-called Comprehensive Plan to End the Gaza Conflict presented on 29 September 2025, with its political and legal framework anchored by UN Security Council Resolution 2803, adopted in November.

This combination is now being used as the reference point for discussions on ending the war, governing Gaza “the day after,” and the possible deployment of an international presence. Yet the further the debate moves beyond the initial ceasefire phase, the clearer the internal contradictions of the plan’s architecture become.

Why the Security Council resolution became the cornerstone

Resolution 2803 matters less for its precise wording than for the fact of its adoption. It transformed a US initiative into an internationally endorsed framework, allowing diplomats to speak seriously about temporary governance mechanisms in Gaza and a potential international stabilization force.

For many states, this was decisive. Without a UN mandate, participation in any Gaza-related mission would have been politically toxic. With such a mandate — even one that is vague and contested — space opens up for diplomacy, coordination and funding.

What the plan consists of, stripped of rhetoric

At its core, the plan rests on three interconnected pillars.

The first pillar is the cessation of hostilities: a ceasefire, the exchange of hostages and detainees, expanded humanitarian access, and basic stabilization on the ground. This phase is often described simply as a “truce,” although it was always conceived as temporary.

The second pillar concerns governance after the war. The plan envisages a transitional civilian administration made up of Palestinian technocrats operating under international oversight. This model is meant to reassure donors that reconstruction funds will not fall under the control of armed groups.

The third pillar is security. It implies dismantling armed rule, primarily that of Hamas, and potentially deploying an international stabilization force to cover the transition period.

It is precisely the second and third pillars that generate the most resistance and controversy.

What is happening in practice by late 2025

According to Western media and diplomatic reporting, Washington is actively pushing forward discussions on forming new governing bodies in Gaza while simultaneously exploring the parameters of an international stabilization force. Consultations with regional partners are under way, including debates on command structures and possible timelines for deployment.

At the same time, mediators are trying to link the launch of a “second phase” of the plan to early 2026, creating the impression of momentum. Yet this movement takes place along a very narrow corridor, where any incident on the ground or a sharp political statement can derail the process.

The core problem: technocrats without power

The formula “Palestinian technocrats” sounds neutral and appealing. It avoids ideological labels, armed struggle and factional politics. In practice, however, it leaves fundamental questions unanswered.

Who appoints these technocrats, and by what procedure. Who can remove them. What mandate they hold, and for how long. How their legitimacy is established in the eyes of Gaza’s population. And most critically, what coercive power stands behind their decisions.

Without answers to these questions, any technocratic administration risks becoming either a decorative body or a constant target of pressure from armed actors. This is why many observers argue that Gaza’s governance cannot be detached from the broader Palestinian political framework, including reform of the Palestinian Authority and the question of representation.

The second problem: disarming Hamas as an unresolved knot

The official logic of the plan assumes that Gaza must cease to be a source of military threat. Yet disarmament does not happen by declaration.

If it is enforced by force, the question becomes who applies that force and who bears responsibility for the consequences. If it is the result of a political deal, the issue shifts to what guarantees and incentives are offered in exchange for relinquishing weapons and power.

So far, public documents deliberately keep this issue vague. This ambiguity creates a serious risk for any international stabilization force, which could find itself caught between opposing sides without clear rules of engagement or solid political backing.

The third problem: political signals that erode trust

Any transition scheme presupposes a gradual move away from military control toward civilian governance. Yet by late 2025, Israeli political discourse continues to produce statements that are widely perceived as contradicting this logic.

High-profile remarks about the possible return of settlements or long-term military presence in Gaza, even when followed by clarifications or denials, undermine confidence in the idea of transferring control. For mediators, this means that even a carefully designed administrative model can collapse if key actors continue to send conflicting signals about Gaza’s future.

The Arab reconstruction framework as a parallel track

Alongside the US-led plan exists a separate Arab initiative for early recovery and reconstruction in Gaza. Submitted as an official document to the United Nations, it emphasizes rapid rebuilding, prevention of population displacement, and Palestinian ownership of the process.

The European Union and several international actors treat this framework as an important complement, or even an alternative, to the American approach. Tensions between the two are evident. The US logic prioritizes security and control, while the Arab framework places greater emphasis on sovereignty and social stability.

Competing interpretations of what is unfolding

One interpretation holds that the plan is gradually taking shape. There is a UN mandate, active mediation, negotiation platforms and initial organizational steps. From this perspective, the decisive moment will be the launch of the second phase and the flow of reconstruction funding.

A second interpretation sees the plan as a façade behind which bargaining and obstruction continue. Every incident and every hardline statement becomes a tool to delay or reshape the process.

A third interpretation argues that the plan can at best freeze the conflict without addressing its core. Without a clear political horizon for Palestinian self-determination, any transitional governance scheme remains fragile and reversible.

Unanswered questions that will determine the plan’s fate

- Who truly governs Gaza during the transition, and on what legal and political basis.

- Who ensures internal security, not just perimeter control.

- How disarmament is carried out, and what happens if it fails.

- Who finances reconstruction and who oversees the use of funds.

- As long as these questions lack clear answers, the roadmap remains closer to a statement of intent than to a functioning mechanism.

What to expect in early 2026

Diplomatic signals from late 2025 suggest attempts to accelerate the move toward a second phase and to formalize the parameters of an international mission. At the same time, the likelihood of a prolonged pause remains high, with each actor operating according to its own logic.

In such a pause, Israel will prioritize security considerations, Hamas will focus on survival, donors will manage risk, and Arab states will concentrate on preventing displacement and preserving Palestinian presence.

Conclusion

The Gaza plan at the end of 2025 is not a single document but a fragile construction composed of a UN Security Council resolution, a US initiative, Arab proposals and a series of diplomatic compromises. On paper, it looks like a pathway out of war. In reality, it collides with three fundamental issues: power, weapons and control.

Until these issues are addressed in a clear and broadly accepted way, the plan will remain both a potential opening toward stabilization and a possible trigger for the next crisis.

Sources and references

- UN Security Council Resolution 2803, November 2025

- White House, Comprehensive Plan to End the Gaza Conflict, 29 September 2025

- Reuters, December 2025 reporting on transitional governance and an international stabilization force

- Reuters, coverage of negotiations on a second phase and timelines for early 2026

- Financial Times, analysis of Israeli political statements on Gaza, December 2025

- Wall Street Journal, reporting on political signals regarding Gaza’s future

- UNISPAL, Arab Plan for Early Recovery and Reconstruction in Gaza, June 2025

- European External Action Service, EU statements on the Arab initiative

- Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, assessments related to Resolution 2803

- Analytical reports by Chatham House, CNAS and ASIL Insights on post-war governance in Gaza